Oyster Duty

To seafood lovers, oysters can be a delicious treat. Others value oysters as a source of precious pearls. But to Demi Johnson, of Gulfport, Mississippi, oysters are environmental superstars. “They’re really important,” the 15-year-old told TIME for Kids. A single oyster, for example, can filter up to 50 gallons of seawater a day, removing algae and harmful organisms. Big groups of oysters form reefs, which provide habitat for hundreds of other sea creatures. Plus, reefs protect against erosion.

Demi learned all of this through oyster gardening. That’s the process of raising oysters in cages for conservation purposes. When she started oyster gardening, in 2022, “I knew absolutely nothing,” Demi says. Today, she’s something of an expert. This school year, Demi earned a master oyster gardener certificate after completing a free course run by the Mississippi Oyster Gardening Program (MOGP). Now she’s spreading the word. “I want others to get into this,” Demi says. “You don’t have to do a lot” to take care of your oyster garden, “but the impact it has for the environment, it’s great.”

BIG SKILLS Demi shows off her master oyster gardener certificate after training with the Mississippi Oyster Gardening Program.

COURTESY SHANTE RICHARDSON

Dock of the Bay

Oysters used to be plentiful in Mississippi’s coastal waters. But their numbers have seen a big drop because of human-made and natural disasters, such as oil spills and hurricanes. That’s according to the Mississippi Department of Marine Resources.

Oyster gardening is a way to help restore the oyster population. “Anyone can get involved,” MOGP research assistant Emily McCay says. All that’s needed is access to a dock or pier. Demi started oyster gardening as a seventh-grade Girl Scouts project. When a hurricane damaged her troop leader’s dock, McCay helped Demi find a new location.

CAGE OF WONDERS One of Demi’s nine cages is pulled from the bay, full of helpful oysters.

COURTESY SHANTE RICHARDSON

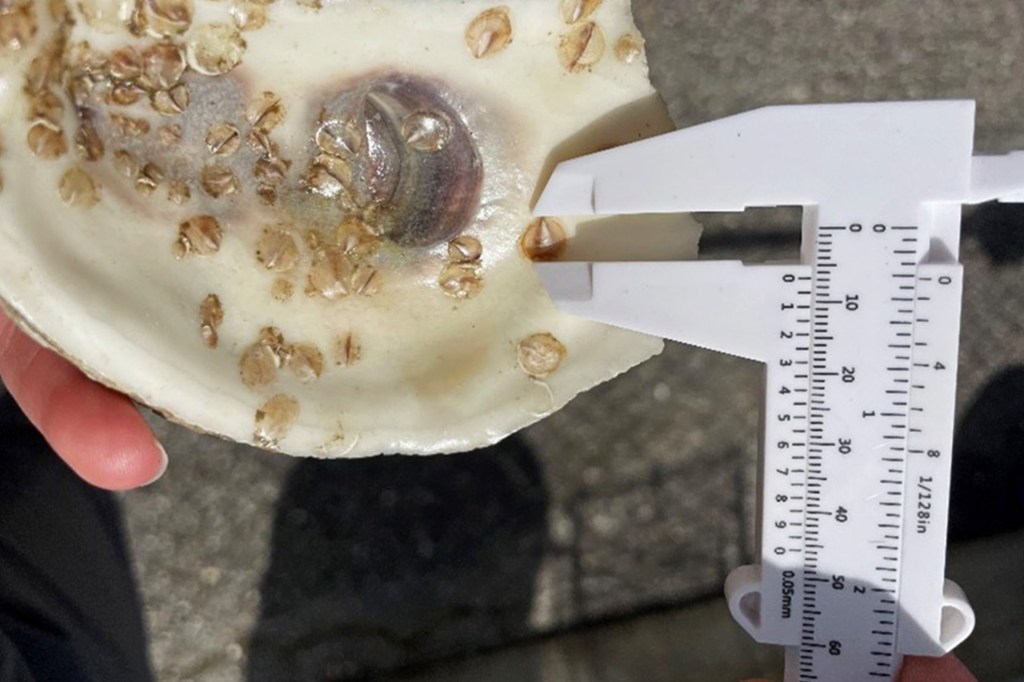

During oyster gardening season, Demi and her mom go to Schooner Pier, on Biloxi Bay. Demi has nine cages. “Once a week I go out there,” she says. She pulls the cages from the water, one by one. She shakes each cage to remove algae and caked-on mud, then checks for predators, such as snails and crabs. Sometimes, she takes her oysters out for inspection. “I just kind of wash them off and just see how they’re doing,” she says.

OYSTER INSPECTION Demi checks on her oysters at Schooner Pier, on Mississippi’s Biloxi Channel.

COURTESY SHANTE RICHARDSON

This spring, oysters grown by Demi and other local gardeners will be big enough to harvest. Demi will go with McCay to pick them up. Harvested oysters are then “planted” on existing reefs in the Mississippi Sound.

NEXT GENERATION Baby oysters, called “spat,” grow in an old oyster shell. With care, they’ll become a large cluster.

COURTESY MOGP

“Demi has gone above and beyond” as a volunteer, McCay says. “She’s actively helping out with so many different aspects of this program.”

Giving Back

Demi has raised more than 1,500 oysters, and has encouraged others to get involved. “She’s a great ambassador for the program,” MOGP leader P.J. Waters says.

GROWING UP A heavy cluster of young oysters is ready to provide a home for other sea life.

COURTESY MOGP

She’s a great supporter, too. Last year, after winning a National Geographic award for her efforts to restore her state’s oyster population, Demi donated the $1,000 cash prize to the MOGP. “We were able to invest that into gear and oysters to grow the program,” Waters says.

Demi is happy to help. “It’s great to be able to do something” that benefits the environment, she says. “It’s a really good feeling.”

Inspired?

Let Demi’s story inspire you to do your part for the environment. Click below for ideas about how you can help protect the planet.