Brooke Tindal used to wake up at 5:50 a.m. and travel 16 miles across New York City to get to middle school. She realized just how much of her day that ate up when schools were forced to go remote during the COVID-19 pandemic. Staying home, Brooke had more time to work on projects for her favorite art class. And she felt less exhausted during the school day.

Brooke didn’t return to the classroom when New York City ended remote schooling in 2021. Instead, she chose a year of homeschooling. Then her mother learned about another option. New York was starting its first public virtual high school. Brooke enrolled in its pilot freshman class.

Now Brooke is 15, a sophomore. “It’s great for me to just stay in one place,” she says, “and do my work at my own pace.”

Back to School

The aftermath of the pandemic made virtual schooling a must for many kids. “There were still a lot of students who were immunocompromised immunocompromised having a weakened immune system (adjective) People who are immunocompromised are more likely to get sick from the virus. , or their families were, and they could not return to the building,” Terri Grey says. She’s the principal of Brooke’s school, Virtual Innovators Academy. “So it really necessitated this permanent option.”

There are 17 teachers and about 200 freshmen and sophomores enrolled at the academy this school year. Another grade level will be added each year. Students meet in person for required state exams. Once a month, they do something fun, like play arcade games or see a Broadway show. But even extracurricular classes, like esports and flying drones, are done from home.

Administrators nationwide cite a bunch of reasons that students might prefer virtual classes. Some kids just concentrate better with a later school start time. Some want to be able to take advantage of other educational opportunities, such as going to a museum at off-peak hours. Some juggle jobs and coursework.

“A lot of parents appreciate the flexibility for their families,” Grey says. “There are students who really thrive learning at home remotely.”

Home Advantage

There are critics. Some are skeptical about whether virtual school can foster group discussions. Others worry that it could create an equity equity justice; fairness (noun) The 1963 March on Washington demanded racial equity in the United States. issue, as some kids can’t afford or don’t have access to the newest technology. (See “Closing the Gap.”) Still, school districts in California, Georgia, Utah, and elsewhere have launched permanent virtual schools.

Virtual Innovators Academy boasts a 96% attendance rate. According to Grey, it has become a haven for kids who are neurodiverse or introverted. Its focus on media and tech could help students land internships managing companies’ social-media platforms.

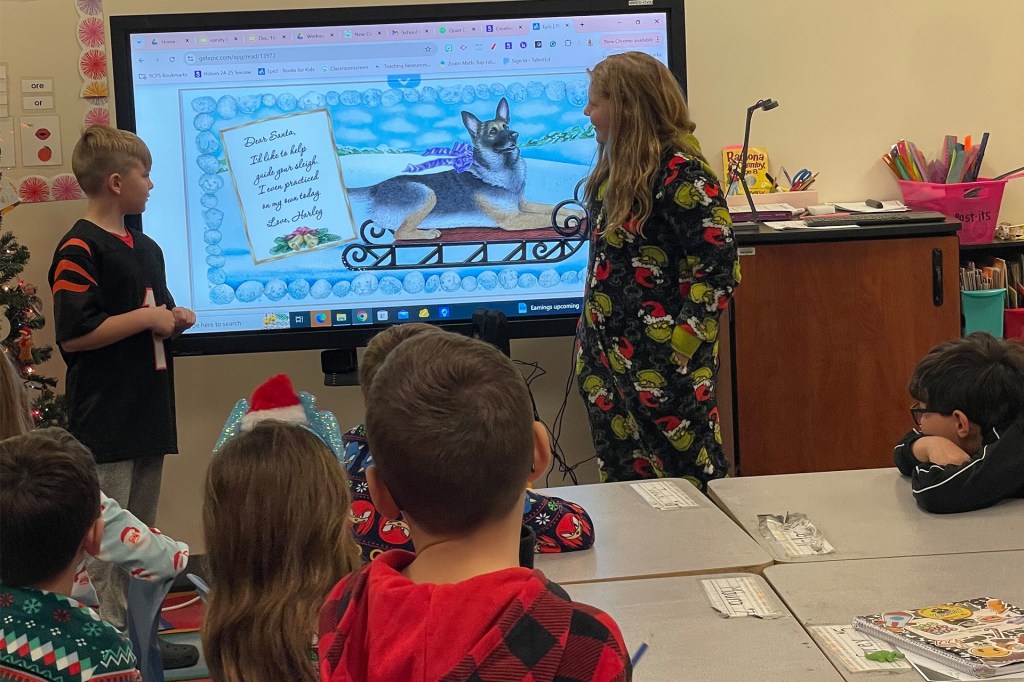

At a K–8 virtual school in Coweta County, Georgia, parents like seeing what their kids are learning so they can help them with their homework. Rebecca Minerd is the school’s principal. “The majority of students are just typical kids, and their parents have made this choice,” she says. “It works well for them.”

Closing the Gap

Students who attend virtual schools depend on fast Internet. But many rural places don’t have the underground cables for it. Around 24% of people in rural areas lack high-speed Internet, compared with 1.7% in cities.

The federal government has invested billions of dollars to address the problem. If the effort pays off, rural areas could improve their economies and provide more educational opportunity. —By Cristina Fernandez