Life in Lava Tubes

Standing in one of Hawaii’s caves, you might think it’s empty. It’s dark, and it’s quiet. Not many plants or animals call this place home. But there’s a lot of life. Most of it you just might not notice.

There might be patches of gold, silver, tan, or pink on the cave walls. Shine a light on them, and water droplets make the patches appear to shimmer. These shining splotches of color consist of microbes microbe a microscopic organism (noun) .

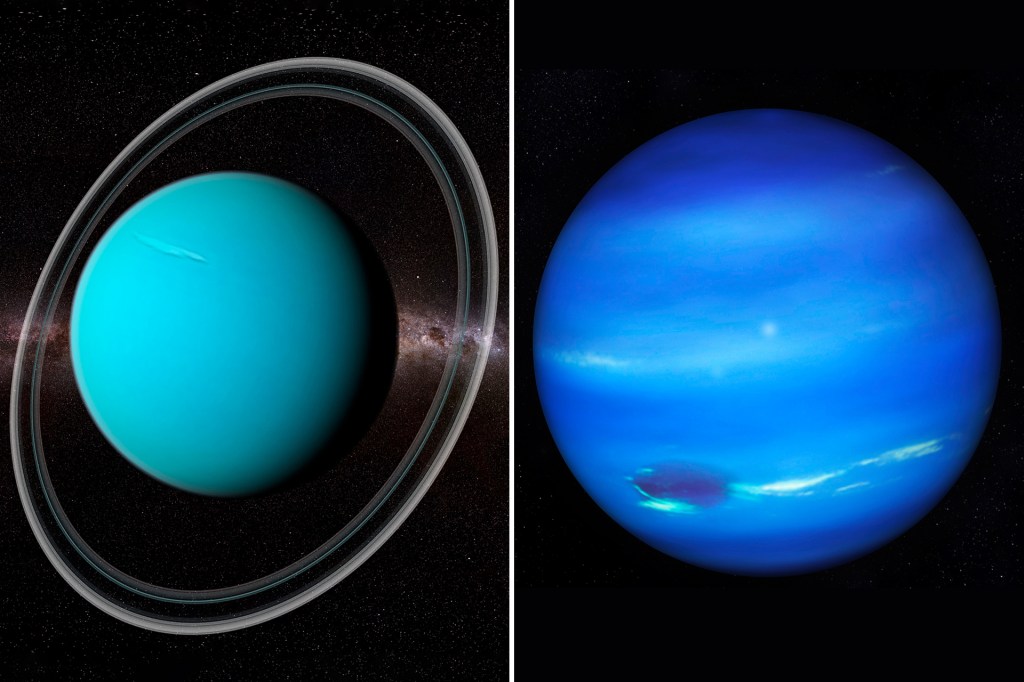

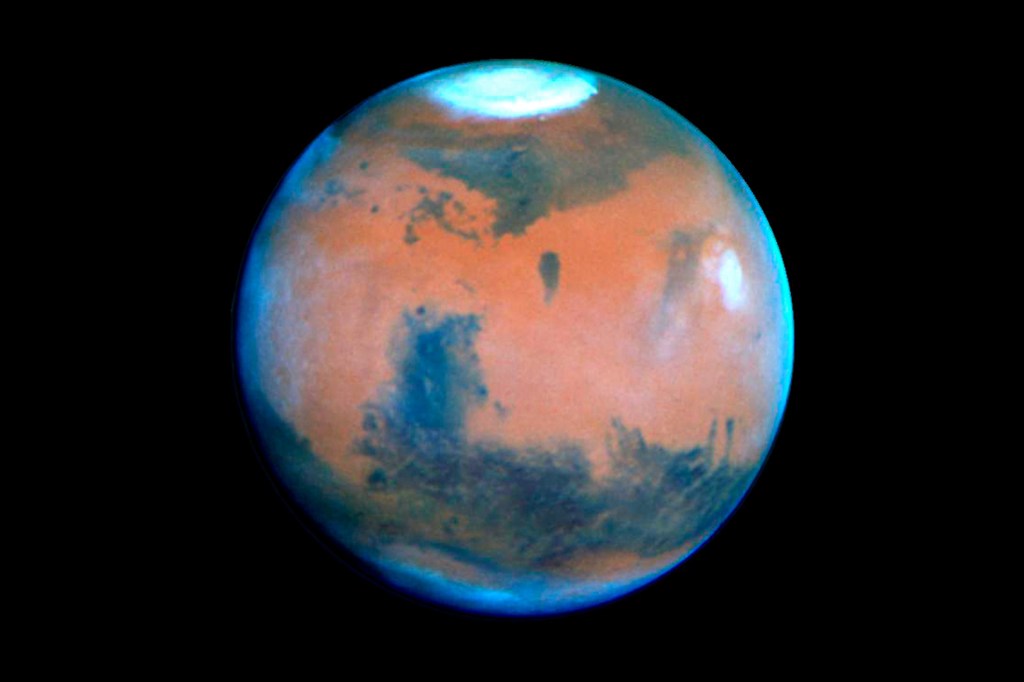

Scientists have been studying these microbes. One reason is that some might be similar to life that once lived on Mars—and maybe still does.

Under the Surface

Many of Hawaii’s caves are lava tubes. They were formed by volcanic activity. After an eruption, hot lava can flow like a river. Over time, air cools the surface, hardening it into black basalt. But underneath, molten lava may still flow. As it drains away below the basalt, it leaves behind an empty tube, or cave.

LIKE A RIVER Hot lava flows after an eruption. As it cools, the surface hardens to a black rock called basalt. If lava continues to flow underneath, a lava tube will be left behind.

JOSIAH HUNT—GETTY IMAGES

Lava tubes exist on Mars, too. So scientists wonder: Do rock-loving microbes also exist there? By studying Hawaiian caves, researchers hope to unlock what life might be like on other worlds.

“It’s a good place to start,” Rebecca Prescott, an astrobiologist astrobiologist a scientist who studies the possibility of life on other planets (noun) at the University of Mississippi, told TIME for Kids. She’s part of a team of scientists who have been looking at microbes in Hawaiian caves. They’ve found some species that hadn’t been seen before.

Microbial Cities

Cave microbes have their own ways of surviving their environment. Some get energy from “eating” the rocks (see “Martian Gardens”). Many of these species are ancient, allowing scientists to understand how microbes lived billions of years ago. “When you walk into a lava cave,” Prescott says, “it’s like you’re walking back in time.”

Scientists are now learning how groups of microbes communicate. Microbes grow in communities that form a slimy film on cave walls. The organisms within a community can “talk” to one another by sending out chemical signals. This may help them tackle tasks together, such as building these slimy cities.

SLIMY CITIES This microbial community, known as biofilm, is growing on the walls of a cave near the Kilauea volcano, in Hawaii.

STUART DONACHIE

And microbe communities might communicate with one another, too, helping them all survive. Prescott and her team hope to learn this microbial language and how it helps these tiny cities thrive—on Earth, and perhaps beyond.

Martian Gardens

Microbes might be important team members on future Mars missions. A one-way trip to the Red Planet could take eight months. Astronauts might need to grow their own food, but not many plants can grow in the planet’s rocky red dirt. Microbes might help.

Here on Earth, some microbes break down toxic chemicals in dirt. Others can “eat” rocks, releasing nutrients to make soil more friendly to plants. Scientists think that microbes can do the same on Mars, helping turn the rocky dirt into rich soils for future Martian gardens to grow.