Gathering Storms

In November, Hurricane Eta made landfall in Central America. The storm caused destruction from Panama to Florida. Two weeks later, Hurricane Iota arrived. It was even more powerful, pouring rain on places that were already flooded. President Juan Orlando Hernández, of Honduras, called Iota a “bomb” that would leave the region in tatters.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season was the most active on record. Iota was the 30th named storm to brew in the Atlantic since May, and the 13th to grow into a full-blown hurricane.

FLOOD ZONE On November 8, 2020, locals in Honduras evacuate a flooded area after Hurricane Eta.

ORLANDO SIERRA—AFP/GETTY IMAGESScientists say climate change is to blame. They don’t know if it’s causing more storms, but data seems to show it’s causing storms to be stronger and more destructive.

James P. Kossin is a climate scientist with the NOAA. He says the increase in greenhouse-gas emissions

greenhouse-gas emissions

EDUARD ANDRAS—GETTY IMAGES

gases released by automobiles and industry that trap heat in the Earth's atmosphere and contribute to climate change

(noun)

Windmills create electricity without producing greenhouse gases.

is changing how storms behave. “These storms have a human fingerprint on them,” he told TIME for Kids.

EDUARD ANDRAS—GETTY IMAGES

gases released by automobiles and industry that trap heat in the Earth's atmosphere and contribute to climate change

(noun)

Windmills create electricity without producing greenhouse gases.

is changing how storms behave. “These storms have a human fingerprint on them,” he told TIME for Kids.

AFTERMATH The heavy rains of Hurricane Eta, in 2020, caused flooding and landslides in Guatemala.

JOHAN ORDÓÑEZ—AFP/GETTY IMAGESStorm Science

As the planet warms, so do its oceans. That’s where hurricanes begin. A storm draws its energy from ocean air. Warmer water provides more energy, which means higher winds. It also means heavier rain. (See “Hurricanes 101.”)

Increased energy is also causing hurricanes to get stronger faster. In August, Laura changed from a tropical storm to a strong hurricane in about a day. It slammed into Texas and Louisiana with winds of up to 150 miles per hour (mph). Laura’s storm surge—a wall of ocean water mainly caused by strong wind—reached 17 feet in places. It was among the highest ever recorded in Louisiana.

DAMAGE AND DEBRIS Hurricane Laura toppled power lines in Lake Charles, Louisiana, on August 27, 2020.

JOE RAEDLE—GETTY IMAGESHurricanes are also sticking around longer to do more damage. Rising temperatures are slowing down westerly winds, which blow constantly around the planet. That makes for storms that move more slowly. In 2017, Hurricane Harvey stalled for days, flooding parts of Texas. “That storm was devastating because it didn’t move,” Kossin says. “It just sat there. And it rained and rained.”

Protection Plans

Storms don’t affect everyone equally, says Dereka Carroll-Smith. She’s an atmospheric scientist at the National Institute of Standards and Technology. She analyzes data on communities that are most affected by hurricanes. This research saves lives by helping cities plan ahead.

HARD-HIT In October 2018, workers survey damage caused by Hurricane Michael in Mexico Beach, Florida.

SCOTT OLSON—GETTY IMAGESCarroll-Smith says areas with a high number of elderly people who cannot easily be evacuated might require one emergency plan. A different plan might be needed in areas where many people live in mobile homes. Recent evacuations were complicated by the pandemic. Shelters couldn’t hold the usual number of people because of social-distancing measures.

“At some point,” Carroll-Smith says, “intense storms are going to be devastating to everyone, unless we make preparations now.”

Reducing greenhouse gases is the first step, Kossin says. “We can stop making it worse. Then we can put our efforts into adapting to the new climate we’re in.”

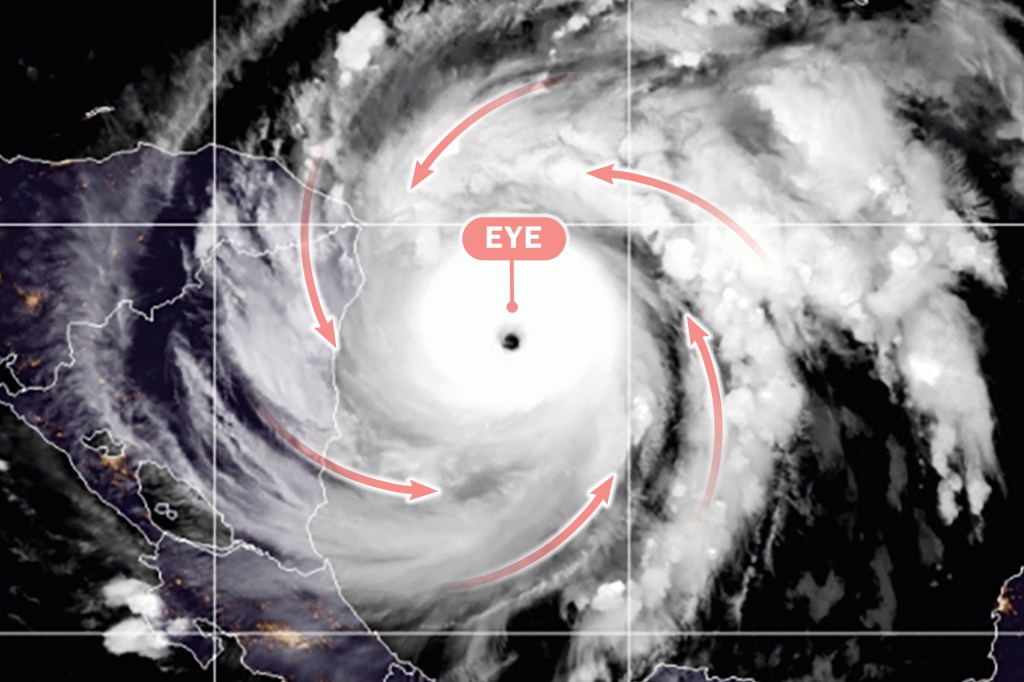

Hurricanes 101

A hurricane is a mass of clouds and thunderstorms rotating around a still center, or “eye.” Think of it as a giant engine that uses warm, moist air as fuel. There’s plenty of that in the Atlantic during hurricane season.

Winds must reach 74 mph before a tropical storm is called a hurricane. Then it’s rated from 1 to 5, depending on wind speed. A Category 5 storm churns at 157 mph or more, destroying homes and making places unlivable for weeks or even months.