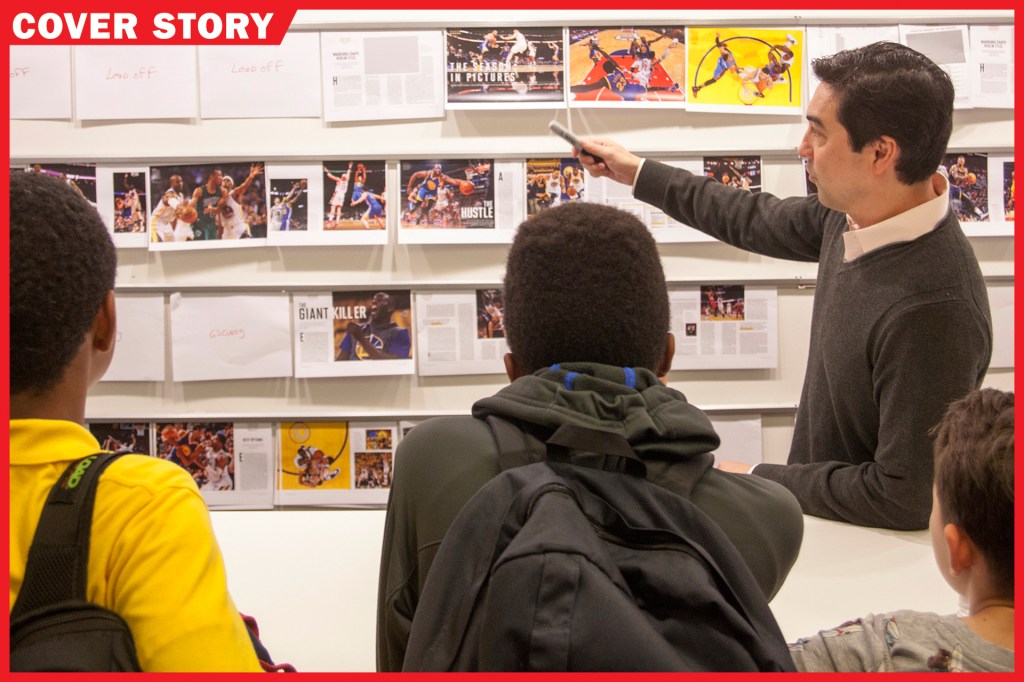

Making Sense of the Media

Students at Capital Preparatory Magnet School, in Hartford, Connecticut, are watching a video of a basketball drill. “Keep track of how many passes the players dressed in white make,” Marcus Stallworth tells them. He is a media-literacy educator. Many of the kids correctly count the number of passes. But they don’t notice a man in a bear suit who moonwalks across the screen.

Why did so many kids miss the furry bear? That’s the question Stallworth asks them. The answer, he says, tells us something important about media literacy.

For Stallworth, the video shows that people miss much of what’s going on around them. “It’s the same when we’re reading information online,” he told TIME for Kids. “It’s important to be aware of the messages, and the ways authors are trying to capture our attention.”

Stallworth is a cofounder of a group called Welcome 2 Reality. He worked with Connecticut lawmakers to pass two far-reaching media-literacy bills

bill

ANDY CLEMENT—GETTY IMAGES

a written description of a new law that is being suggested, which lawmakers must vote on

(noun)

Senators voted to approve the bill.

.

ANDY CLEMENT—GETTY IMAGES

a written description of a new law that is being suggested, which lawmakers must vote on

(noun)

Senators voted to approve the bill.

.

BREAKING NEWS Media literacy helps kids identify trustworthy news sources.

NATAKI HEWLING FOR TIME FOR KIDS

Connecticut is one of several states to strengthen media-literacy instruction. Others include Florida, Minnesota, and Washington. All are part of a movement supported by the advocacy

advocacy

SAWITREE PAMEE—EYEEM/GETTY IMAGES

the act of supporting a cause or proposal

(noun)

Abram is known for his advocacy of recycling.

group Media Literacy Now.

SAWITREE PAMEE—EYEEM/GETTY IMAGES

the act of supporting a cause or proposal

(noun)

Abram is known for his advocacy of recycling.

group Media Literacy Now.

“It’s important for children to be able to navigate all this information,” state senator Terry Gerratana says. She proposed both of Connecticut’s bills. “Even as an adult, it’s very hard to sort it all out.”

Fact or Fiction?

The rise of fake news during the 2016 election fueled

fuel

KIDSTOCK/GETTY IMAGES

to add strength or support to

(verb)

The bad grade fueled Shia's determination to ace the test.

interest in media literacy. “Four years ago, people were not returning my calls,” says Michelle Lipkin. She leads the National Association for Media Literacy Education. “I would have to spend 30 minutes explaining what we do. Now people are seeing media literacy [as a] solution.”

KIDSTOCK/GETTY IMAGES

to add strength or support to

(verb)

The bad grade fueled Shia's determination to ace the test.

interest in media literacy. “Four years ago, people were not returning my calls,” says Michelle Lipkin. She leads the National Association for Media Literacy Education. “I would have to spend 30 minutes explaining what we do. Now people are seeing media literacy [as a] solution.”

DIGITAL AGE Many kids read news on devices that make information available 24/7.

SAHA ENTERTAINMENT/GETTY IMAGES

What is media literacy, exactly? “It’s thinking critically about the information we see, read, and hear,” Kelly Mendoza of Common Sense Education says. The goal is to give students the tools to identify credible

credible

MIKAEL VAISANEN—GETTY IMAGES

believable

(adjective)

Maria said her dog ate her homework, but Mrs. Mable did not find the story credible.

sources. A 2017 study found that just 44% of kids feel they can tell real from fake news.

MIKAEL VAISANEN—GETTY IMAGES

believable

(adjective)

Maria said her dog ate her homework, but Mrs. Mable did not find the story credible.

sources. A 2017 study found that just 44% of kids feel they can tell real from fake news.

Not every state has gone as far as Connecticut and others to support media literacy. Lawmakers in Arizona and Virginia proposed bills. But laws have not yet been passed.

Still, Lipkin is hopeful. “Progress has been slow but steady

steady

PORTRA/GETTY IMAGES

in a fixed position or direction, or at a fixed rate

(adverb)

Rudy no longer wants to practice his violin, but Horacio's interest in the instrument has held steady.

,” she says. “We need states and the country [to see the importance] of these skills.”

PORTRA/GETTY IMAGES

in a fixed position or direction, or at a fixed rate

(adverb)

Rudy no longer wants to practice his violin, but Horacio's interest in the instrument has held steady.

,” she says. “We need states and the country [to see the importance] of these skills.”

A Free Press

The Newseum (above), in Washington, D.C. is a museum about news. It works to increase understanding of the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment. The amendment guarantees five freedoms. One is freedom of the press. Many countries do not have a free press. Their government controls what journalists can report.

“It’s the first amendment for a reason,” Newseum spokesperson Sonya Gavankar says. “It’s what our freedom is based on.”

Assessment: Click here for a printable quiz. Teacher subscribers can find the answer key in this week's Teacher's Guide.