From Ranch to Lab

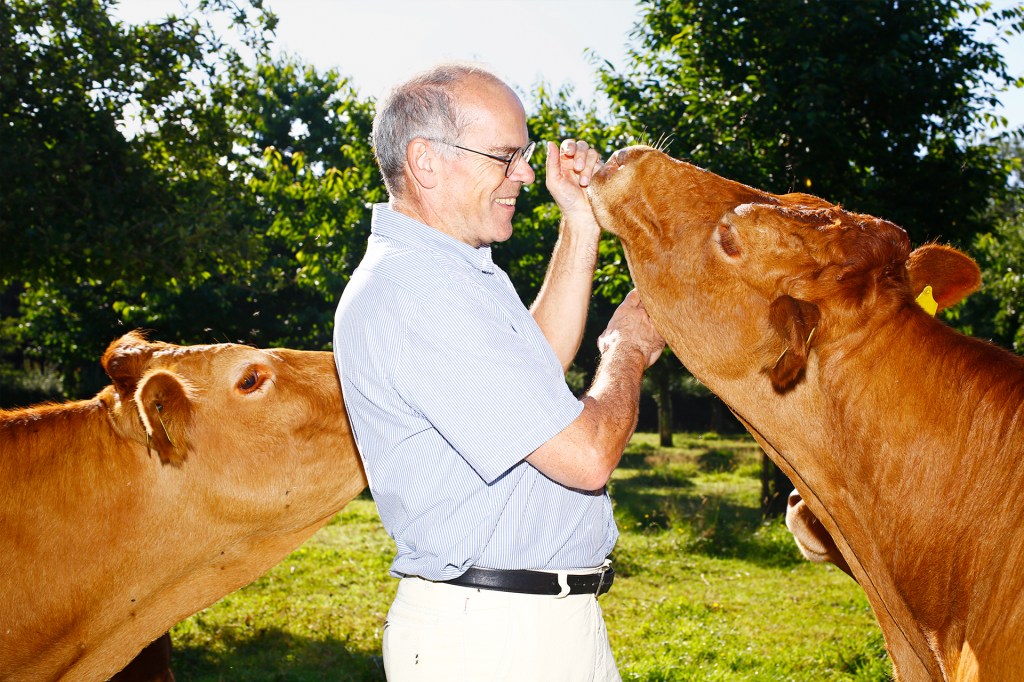

Brown cows roam the meadows of a farm in the Netherlands. They are Limousins, a breed known for the quality of its meat. Every few months, a veterinarian makes a tiny cut in a cow’s flank, removes a sample of muscle, and stitches the cow back up. A dab of painkiller on the skin means this doesn’t hurt much.

At a nearby lab, scientists put the samples into steel containers with a nutrient broth. The cells grow and multiply. This process creates new muscle. And from that, something like hamburger meat is produced. It’s a lot like the stuff you buy at a supermarket.

ON THE FARM Mark Post, of Mosa Meat, greets Limousin cows on a farm in the Netherlands.

RICARDO CASES FOR TIMEBy 2030, meat grown in a lab could account for .5% of the world’s meat supply, according to a recent report. One day, it might even replace factory farming, in which many cows are raised in small spaces. This could solve one of the big problems of our time: how to feed a growing global population without increasing greenhouse-gas emissions.

Every year, raising livestock for food causes up to 14.5% of the planet’s greenhouse-gas emissions. That system is unsustainable

unsustainable

VIEWSTOCK/GETTY IMAGES

unable to be continued without doing permanent damage

(adjective)

Working long hours every day of the week was unsustainable for Johnny.

, biologist Johanna Melke says. She works for a Dutch company called Mosa Meat. It grows meat in a lab. “People want to eat meat,” she says. “This is how we solve the problem.”

VIEWSTOCK/GETTY IMAGES

unable to be continued without doing permanent damage

(adjective)

Working long hours every day of the week was unsustainable for Johnny.

, biologist Johanna Melke says. She works for a Dutch company called Mosa Meat. It grows meat in a lab. “People want to eat meat,” she says. “This is how we solve the problem.”

IN THE LAB A scientist at Mosa Meat views cell samples with a microscope.

RICARDO CASES FOR TIMEAn Easier Choice

Nine years ago, Mosa cofounder Mark Post helped introduce the first lab-grown hamburger. Today, more than 70 companies are making lab-grown meats that include beef, chicken, tuna, shrimp, and even mouse (for cat treats). (See “Something Fishy.”) According to the World Resources Institute, global demand for meat will nearly double by 2050. Lab-grown meat could soon be a $25 billion industry.

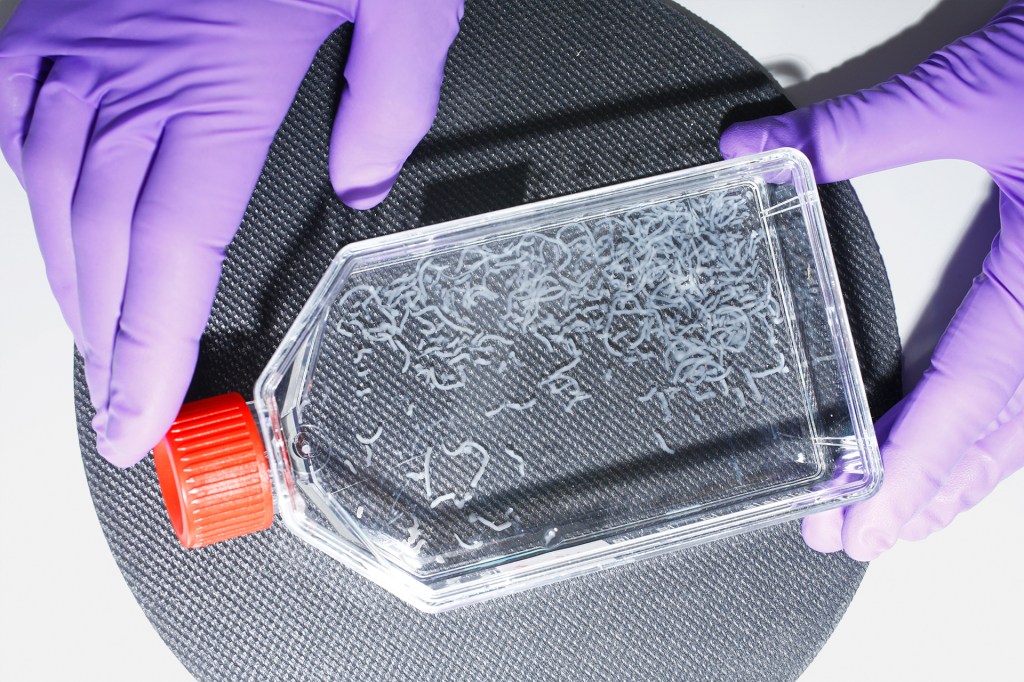

BURGER-TO-BE These are threads of fat. They’re made by growing cow cells in a lab. They’ll be used to make meat.

RICARDO CASES FOR TIMEPost says a half gram of cow muscle could possibly be used to make up to 4.4 billion pounds of beef. That’s more beef than Mexico consumes in a year. Growing meat could be as effective as solar and wind energy are at fighting climate change, he says.

“I can’t give up meat, and most people are like me,” Post says. “So I wanted to make the choice for those people easier: to be able to keep on eating meat without all the negative [consequences].”

In Development

So far, no company has figured out how to produce large amounts of lab-grown meat and bring down costs. Three chicken nuggets by the company Eat Just cost about $17 at a restaurant in Singapore. That’s a lot more than regular nuggets cost at McDonald’s.

BY DESIGN This machine creates custom-made parts for Mosa’s work.

RICARDO CASES FOR TIME

Cattle ranchers also stand in the way. The United States Cattlemen’s Association asked the government to set rules. Ranchers want the terms beef and meat used only for products that come from animals raised in a traditional manner. That could make it harder to sell meat from a lab. “The terms you can use make a critical difference,” says market researcher Michael Dent. “Who’s going to buy something called ‘lab-grown cell-protein isolates

isolate

PAUL HENNESSY—NURPHOTO/GETTY IMAGES

a small part separated from something larger

(noun)

The scientist analyzed isolates of a virus strain in his lab.

’?”

PAUL HENNESSY—NURPHOTO/GETTY IMAGES

a small part separated from something larger

(noun)

The scientist analyzed isolates of a virus strain in his lab.

’?”

Still, Mosa says its product can win people over, whatever it’s called. “It was so intense—a rich, beefy, meaty flavor,” says scientist Laura Jackisch, who gave up eating animal products years ago. “I started craving steak again.”

Something Fishy

Some of the fish we eat is caught faster than it can be replenished. Overfishing can wipe out whole species.

Avant Meats makes fish meat in a lab. This includes fish maw, a part of the fish that’s popular in China. Lab-grown maw feels like real fish before it’s cooked, chef Eddy Leung says. “But when you eat it, it doesn’t yet have the kind of stickiness the real ones do.” —By Amy Gunia for TIME, adapted by TFK editors