Collision Course

Sixty-six years ago, there was one human-built object in Earth’s orbit. It was Sputnik, the world’s first satellite, launched in October 1957. Try to guess how many human-made objects are circling the planet now. Ready?

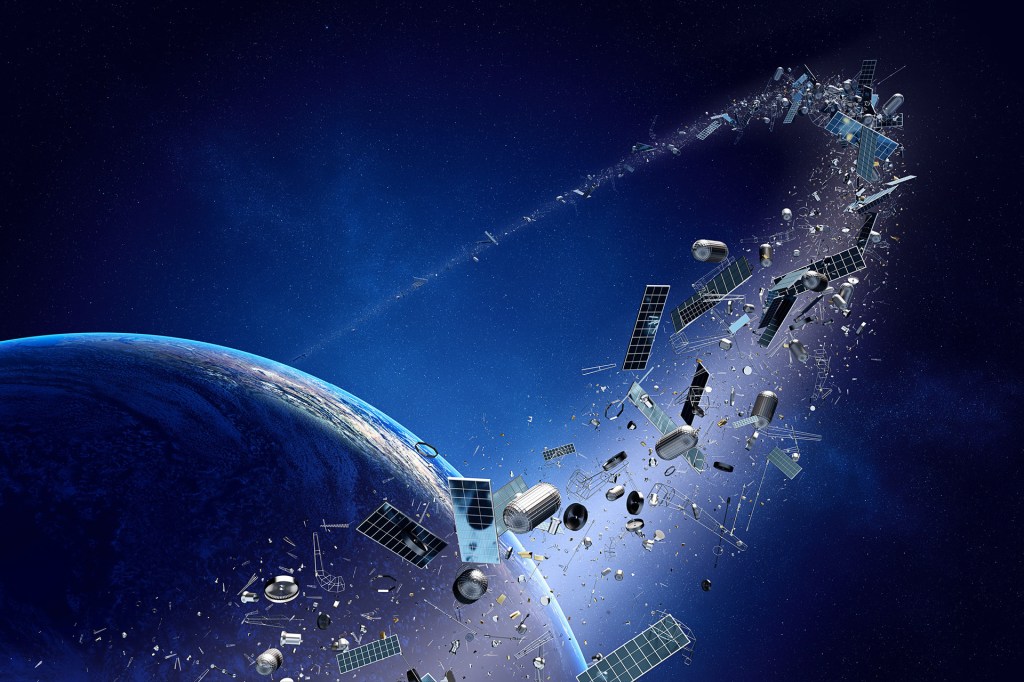

Your answer is wrong, unless you guessed 100 trillion. That’s a jaw-dropping number. It was provided by an international team of researchers writing in the journal Science. For years, this junk has formed an ever-growing mass near Earth. It’s a danger to spacecraft. The researchers are calling for a global treaty to limit the number of satellites and the amount of rubbish in space.

“There is no international treaty treaty an official agreement between countries or parties (noun) My sister and I made a peace treaty and promised to quit fighting. that seeks to minimize orbital debris,” the scientists write. They say that must change—and fast. “We need collective cooperation, informed by science, to develop a timely, legally binding treaty to protect Earth’s orbit.”

PASSING DANGER A piece of debris sails high over Earth. It was spotted by the Space Shuttle Columbia in 1986.

SPACE FRONTIERS/ARCHIVE PHOTOS/HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGESHigh–Speed Danger

There are 9,000 active satellites in orbit, the scientists report. That could grow to more than 60,000 by 2030. The rest of that 100 trillion figure includes everything from used-up booster rockets and stray bolts to metal flecks and paint chips.

Don’t think a paint chip is harmless. Traveling at 17,500 miles per hour, it can strike a spacecraft hard. The International Space Station is dotted with dents and holes. Astronauts often take shelter in an attached spacecraft to wait out a passing swarm of space debris. That way, if the station is severely damaged, they can bail out in a hurry.

BROKEN PART In 1997, this Russian space station was damaged in a collision with space junk.

NASA/GETTY IMAGESAll of this debris will eventually fall to Earth and burn up in the atmosphere. But we’re replacing the junk more quickly than it’s falling.

OUT OF THE SKY A hunk of space junk (left) stands in a field in Australia in July 2022. It burned as it fell through Earth’s atmosphere.

BRAD TUCKER—AFP/GETTY IMAGES IMAGESFinding a Fix

The mess we’ve made in space is like the mess we’ve made in the oceans. Think of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. It’s a mass of floating junk twice the size of Texas. We’ve had centuries to foul the oceans. But it has taken just decades for us to do the same in space.

That’s why the Science authors include experts in satellite technology and in ocean plastic pollution. “As a marine biologist, I never imagined writing a paper on space,” Heather Koldewey writes. She works at the Zoological Society of London. Cleaning up space, she says, has a lot in common “with the challenges of tackling environmental issues in the ocean.”

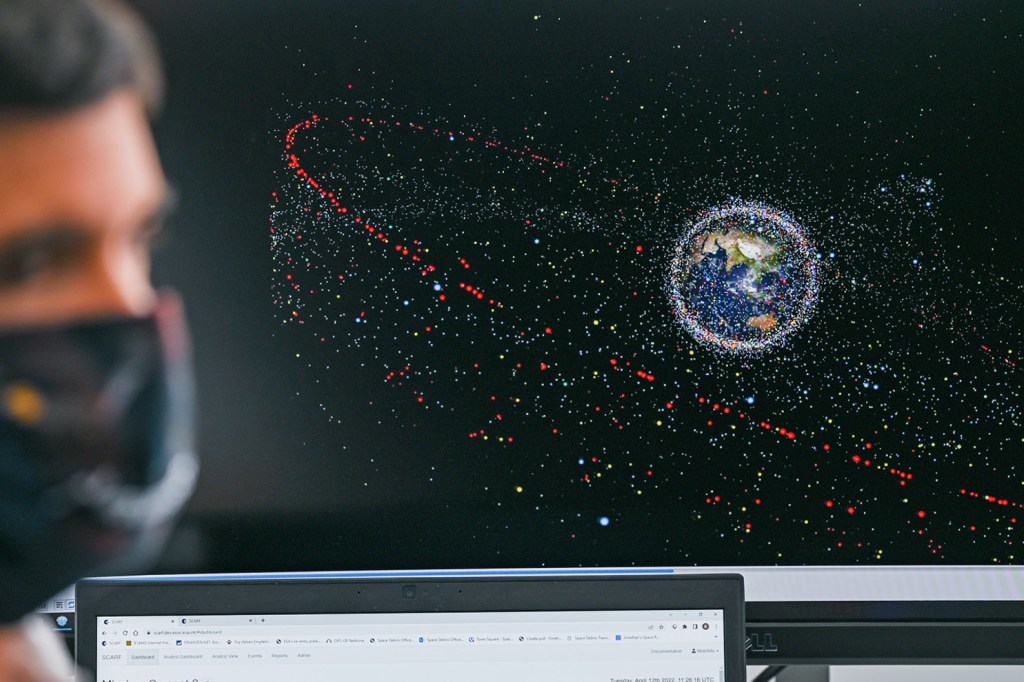

SCREEN SHOT A monitor at the European Space Agency shows debris floating in Earth’s orbit.

ARNE DEDERT—PICTURE ALLIANCE/GETTY IMAGESKoldewey and her coauthors see hope for space. They look to the effort to clean up the oceans. In March 2022, 170 countries signed a global plastics treaty at the United Nations. This is an agreement to dump less plastic in the oceans and get rid of what’s already there. There could be similar rules for how much debris a launch can create. Old satellites could be taken out of space. And technologies could be developed for cleaning up the rubbish. (See “Trash Collector.”)

Coauthor Moriba Jah is an aerospace engineering professor at the University of Texas at Austin. “Marine debris and space debris,” he writes, are both a human-made “detriment detriment damage; harm (noun) Nutritionists say eating too much sugar is a detriment to our health. that is avoidable.”

Trash Collector

In 2018, scientists on the International Space Station tested the RemoveDebris satellite. In this picture, robotic arms push the device into space. The satellite measures about three feet on each side. It uses a 3D camera to track the location and speed of floating debris. Then it fires a net to capture the junk, which falls and burns up in the Earth’s atmosphere.

The test was a success. It may have brought the world a step closer to a safer orbit.